Custer’s Last Gun: Webley RIC Revolver

By Garry James

The RIC was a rugged, robust revolver, though the .442 round (firing a 220-grain lead bullet at some 700 fps for a muzzle energy of 239 ft-lbs) was underpowered compared with the .45 Colt, which blew out its 255-grain bullet at well over 800 fps for a muzzle energy exceeding 400 ft-lbs.

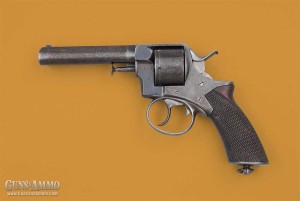

Typical Webley & Scott winged-bullet markings found on Webley revolvers of the period (and later). Note the front locking lugs on the RIC’s cylinder, which were indicative of a First Model.

Still, it was also possible to see the attraction of the Webley with its rapid-firing double action. Custer, being an avid firearms buff and something of a gadgeteer, would have certainly found merit in this handy little sixgun.

In a letter written years after the battle, Lt. Edward Godfrey, of K Company, 7th Cavalry, mentions that during the expedition that culminated in the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Custer was carrying “two Bulldog self-cocking, English white-handled pistols with a ring in the butt for a lanyard.”

As we have determined, Custer’s RIC was blued with walnut grips and no lanyard ring, so it’s my guess that Godfrey confused the Webley with the Smith & Wessons, which were plated and had pearl grips, though they didn’t have lanyard rings. But to be fair, he did describe Custer’s other gear pretty accurately: “a Remington rifle, octagonal barrel…a hunting knife in a beaded, fringed scabbard; and a canvas cartridge belt.”

During the Reno Court of Inquiry, which took place 20 years after the event, much testimony, including Godfrey’s, was contradicted and confused, so there is still room for error. As the Webley was much smaller and shorter than the issue Colt, the “Bulldog” appellation is more or less appropriate, especially to an American. Also, the fact that all of the guns seen in the gun rack are currently accounted for—with the exception of the Webley—adds more evidence to the assumption that the RIC was the gun Custer probably had with him at Greasy Grass.

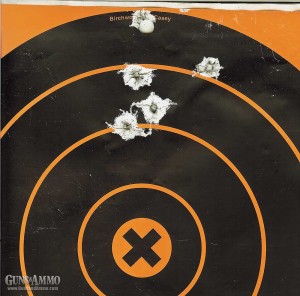

The author found the .442 RIC to be very pleasant to shoot, but it was significantly less potent than the U.S. Army-issue .45 Colt single action.

To date, no .442 cartridge cases have been found on the battlefield. But as things were getting pretty hot and heavy as the Indians approached the troopers at handgun range and the RIC’s ejection system (which consisted of a rod that had to be pulled free from a channel in the cylinder pin and then rotated to the right to poke out individual cases) was not as efficient as that of the Colt, there’s a good chance that Custer might not have had time to fire off more than a single cylinderful. This means that the empty cases could have still been in the gun when it was taken from the commander’s dead body by one of Sitting Bull’s best.

Offhand double-action groups at seven yards ran around three inches.

For a number of years I’ve owned a .442 First Model RIC virtually identical to the one seen in Custer’s study, with the exception that mine has a lanyard ring. Sights are similar to those of a Colt, involving a rear groove in the topstrap and rounded front blade.

It was retailed by R.S. Garden, Piccadilly, London, and is in excellent mechanical shape. The bore is virtually perfect. Recently, I put together some black-powder .442 rounds as close to original specs as possible using modified .44 Special cases and 220-grain lead bullets cast from a mold made by Rapine Bullet Mould Manufacturing (215-679-5413).

Groups were fired double and single action at seven and 25 yards, and though they shot slightly high, they were certainly respectable, coming in at an average of three inches at seven yards and 53/4 inches at 25. Recoil was light, and when one compares the .442 RIC with the rip-roaring .45 Colt, there is really no contest as far as puissance is concerned. Also, I would say that it took about twice as long to eject spent cases with the RIC than with a Colt SAA.

The author found that poking out spent cases with the RIC was not as easy as with a Colt SAA.

While the Webley might have had a certain novelty value, as far as an effective stopper against Custer’s formidable foe at the Little Big Horn, it was, to my mind, severely lacking. Perhaps Custer didn’t think he was going to have to use a sidearm all that much during the campaign, or perhaps he just wanted to give it a field test of his own. When one realizes he owned the gun for a good six years prior to the battle, you might expect he would have been familiar with its shortcomings, if he realized it had any. It must be admitted, though, that the science of ballistics was not as sophisticated then as it is now, so Custer could possibly have felt he was adequately armed with the RIC.

In any event, it is a mystery that will never be completely solved. The chances of the gun turning up with decent provenance after all these years are virtually nil. Unearthing spent .442 cases on the battlefield would certainly help answer any questions, but as the round was not unknown in the West at the time, there is no way of conclusively proving they came from a revolver actually fired by Custer.

Still, the whole question just adds that much more interest to the whole affair that was the Battle of the Little Big Horn and to the mystique of the commander who led his command to defeat in one of the most famous battles in American history.

The author would like to thank noted Custer authority Glen Swanson for his help in the preparation of this article. His book, G.A. Custer, His Life and Times, is highly recommended for those wishing to delve into the Custer legend. It is available on his website at

The author would like to thank noted Custer authority Glen Swanson for his help in the preparation of this article. His book, G.A. Custer, His Life and Times, is highly recommended for those wishing to delve into the Custer legend. It is available on his website at

George Armstrong Custer was one of the most colorful and controversial American military figures of the 19th century. Remembered mostly for his devastating defeat by Lakota and Northern Cheyenne at the Battle of the Little Big Horn (or “Greasy Grass,” as the Indians called it), in fact he was actually an extremely able cavalry commander—bold, brave and able to make quick, prudent decisions, as he had proven in the Civil War and subsequently on the Western Plains.

Custer had the ability to inspire fidelity and enmity with both superiors and subordinates. His death and the destruction of his command at the Little Big Horn in late June 1876 was an incredible shock to the nation, which was preparing to celebrate its centennial, and caused many to reevaluate their opinions and policies toward Native Americans.

During the course of his career, Custer owned a number of military and sporting arms. He was an avid outdoorsman and excellent shot who appreciated a reliable, effective firearm.

The epitome of the “self-cocking” Bulldog, the Royal Irish Constabulary revolver was a rugged double action in .442.

At the time of the Little Big Horn, Custer’s command, the 7th U.S. Cavalry, was armed with …read more

Source:: Guns and Ammo

Leave a Reply